| Hani Hurani, 13.9.21, Al-Arabi Al-Jadid,شرقي الأردن مطلع القرن العشرين عبر عدسة خليل رعد | | | | The exhibition will be shown at Gutman Art Museum until October 2nd 2010 | | | | To purchase the book (in Hebrew) | | | Download the Article: "Resilient Resistance: Colonial Biblical, Archaeological and Ethnographical Imaginaries in the Work of Chalil Raad (Khalīl Raʿd), 1891–1948." Imaging and Imagining Palestine, edited by Karène Sanchez Summerer and Sary Zananiri, 185-226. The Netherlands: Brill, 2021

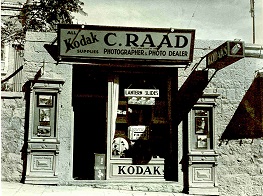

The book and exhibition Chalil Raad (Khalil Ra’d), Photographs 1891-1948 are the first in Israel and the world dedicated to the work of Chalil (or Khalil) Raad. Raad, one of the firsts Arab photographers that were active in Palestine (probably the first), and one of the most important of the Arab photographers who travelled and photographed in the Middle East, was born in 1869 in Lebanon, and sent as a child to the school of Bishop Gobat in Jerusalem. He studied photography with Garabed Krikorian, one of the first local Armenian photographers. In 1890 Raad travelled to study photography in Basel, following his high school teacher Keller from Basel who came to Jerusalem (in the 1880s) to study Arabic for his doctoral dissertation. Radd studied photography and helped his teacher to translate texts from Arabic. In 1891 he began to photograph independently, and four years later opened a photography studio in Jerusalem on Jaffa Road, outside the walls of the Old City. A few years later he advertised his work in the Hebrew newspaper Havatzelet [lit. Lily]: “to inform, to announce, and to make known - those desiring photographed pictures of any kind, of the most refined, and at a reasonable price, can apply to me, the undersigned, and I am prepared at all times to fulfill the wishes of any of my admirers, in the best manner possible!” (1899). At the turn of the century he was appointed photographer to The Kingdom of Prussia, giving him immunity - a status that allowed him to travel and photograph in relative freedom. Apparently he was also the official Turkish photographer and documented local events of the First World War. At the Eve of WW1 Raad travelled again to Basel "to learn the latest techniques then being developed" (Al-Hajj 2001, 35) and met there his future wife, Annie Muller who worked for Keller.

Raad’s importance in the history of local photography is significant. He photographed for more than six decades and produced an impressive and comprehensive body of work that tells the story of the region from a unique point of view. He was involved in many local photography activities and his studio also provided photographic services for foreign photographers who came to photograph in the Holy Land - such as the artist and photographer, Ephraim Moshe Lilien, and the many Western archeological and travel expeditions that carried out excavations in the country. In the period he was active, Raad’s photographs were published in many books and were recognized throughout the world.

The core of Raad’s work was dedicated to describing the rich life of the Palestinian community. While he documented the Near East and the local communities of the country, including the old and new Jewish population, he gave the Palestinians a presence and visibility rarely seen in foreign photographs of the country in the late 19th century or in Jewish Zionist photographs of the early 20th century, which concealed and excluded them in a tendentious manner. His work provides a comprehensive description of Palestinian life in the country in all its urban, cultural, economic and political richness. Raad loved the country, its history, its illustrious past, its wild scenery and landscapes, its strength and spiritual richness, its geography, its cultural and social history, all of which he expressed in his work.

Raad began to photograph in Palestine and the region in a reality steeped in western colonial influence in general and colonial photography in particular. Foreign photographers preferred to document biblical places, holy sites and landscapes of the country through a Eurocentric gaze. In this way they provided “visual proof” of a biblical world frozen in time and of an undeveloped Holy Land ready for western conquest. The Orient, created as an imagined reality by the power of European authority, was deciphered by it using western codes, mainly serving its imperialistic aims. As a Christian educated in the Bishop’s School in Jerusalem, Raad, to a degree, was influenced by the biblical worldview and integrated some of its features into his photographs, building a “mixed” body of work, a hybrid. As a local resident who gave significant representation to the Palestinian population, he established an alternative form of representation to the colonial model, while at the same time adopting different aspects of this model – described by Albert Memmi and Frantz Fanon in their criticism on colonialism. Primarily Raad’s work indicates how the local inhabitants responded to and experienced the prevailing western viewpoint forced on the region, and later expresses the complexity and duality of the relationship that was born in the wake of the colonial situation. Furthermore, as long as Palestinian life and identity was based in the country, he gave them significant representation, which Arab and Palestinians researchers portrayed as an indication of his opposition to the colonial situation. Memmi describes this situation as another stage in the development of colonial relationships. The exhibition seeks to give expression to both of these central aspects.

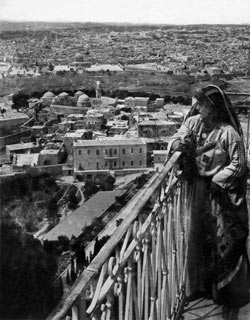

In addition, the exhibition designates chapters to the Near East, to Raad’s typological work (close-ups of archeological remnants in Palestine and the Near East, interiors and exteriors of architectural spaces, close-ups of structures, sites,and flowers), to photographs of the city of Jerusalem seen with love throughout his photographs, and photographs of the Jewish population of Palestine.

Raad lived in the country for seven decades and linked his destiny to the destiny of the country. Therefore, he is considered as the first Palestinian photographer active in the region. In May 1948, a few days before the British Mandate ended and following an escalation of the national conflict, he fled with his wife to Jericho. Prevented from returning to their home in Jerusalem, like many other Palestinians, they became exiles in Lebanon, where he died in 1957.

| | | | The Palestinian Community | | | In contrast to the image of a sleepy undeveloped, abandoned and backward country with a handful of inhabitants – present in colonial photography and later in Zionist photography of the period – Raad dedicated a large portion of his work to describing the rich and developed life of Palestinian residents of the country in towns and villages. In documentary, staged or partially staged photographs he showed the country throughout its length and breadth from an Arab and Palestinian perspective: portraits, daily life, urban and rural development, religious ceremonies, national events, commerce, fishing, agriculture, education, culture, processions, customs and the like. Many of his photographs are filled with national grandeur and describe the Palestinian population up until the 1948 war. These images, which have been erased from the visual lexicon of the region, open a window on the world of the Palestinians who were in the country up until 1948 - a world rarely observed by Israeli society. Based on the research of philosophers and academia, this significant representation of Palestinian life and identity can be defined as one of the stages in Raad’s resistance to the colonial situation.

| | | | The Holy Land | | | As a Christian who grew up on the New Testament and the biblical narrative, Raad was drawn to the aura and charm radiated by this ancient story, and repeatedly described scenes that helped to construct a biblical and holy image of the country. He was also influenced, to some degree, by the visual and content-related aspects of western photography with regard to the country and its surroundings that were widely marketed in the west through a variety of different methods. Like the foreign photographers active in the country in the 19th century, Raad gave a central place in his work to the Bible and the ancient history of the land, with their significance and different messages, and over the years built a“ Holy Land” collection. His stationery from 1914, for example, displays the caption: Photographer of “historical sites” and “characters from the Land of the Bible,” and in 1920 he marketed his work in a similar manner - “C. Raad, photographer, Jerusalem … A large collection of lantern slides and photographs of biblical & historical places in Palestine & Syria” (Palestine Directory). Furthermore, like his western colleagues who photographed in the Holy Land in the 19th century, Raad also photographed places mentioned in the New Testament that had significance for Christian believers, like the house of Simon the Tanner in Jaffa, (Acts of the Apostles, Ch. 9: 39-43, Ch. 10: 6), and the Inn of the Good Samaritan (the Gospel according to Luke Ch. 10: 25-37) as well as churches and sites with Christian religious-historical importance, such as the Spring of the Virgin Mary in Nazareth. The series Via Dolorosa describing the stations and the path walked by Jesus resembles the series Stations of the Via Dolorosa photographed by the Bonfils Family in the 1870s. Like foreign photographers, he usually added captions taken from the New Testament to his photographs, thus confining the photograph to its religious-historical connection, also when this was not immediately apparent. For example, the photograph depicting fisherman on the shores of the Sea of Galilee (photograph 336a) is accompanied by the caption Follow me and I will make you fishers of men, which hints at “Come ye after me, and I will make you to become fishers of men” (the Gospel according to Mark Ch. 1:17).

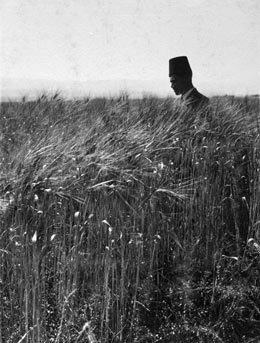

Raad also photographed places referred to in the Bible – those where biblical heroes had lived or important events had occurred. The biblical context was created through the positioning of the figures and the accompanying caption. For instance, the photograph of a Palestinian youth seated against the scenic background of Zorah carries the caption Zorah, the House of Samson, and the photograph of a woman in a grain field is named Ruth the Gatherer (Ruth Ch. 2:2-3). Photographs of the Spring of Gideon (the reference is to the Ein Harod Spring, known from Gideon’s war with the Midianites, Judges Ch. 6 -7), and Joseph’s Pit - Dothan, the Pool of Siloam and Absalom’s Pillar, also refer to events and place from biblical times, and are seen in foreign photographs from the west as well. Raad’s work to some extent focuses attention – even if unconsciously – on the way local artists responded to the western colonial worldview that was forced on the region. Thus, this chapter enables to demonstrates the criticism against the oppressive influence of colonialism evoked in the work of researchers and philosophers.

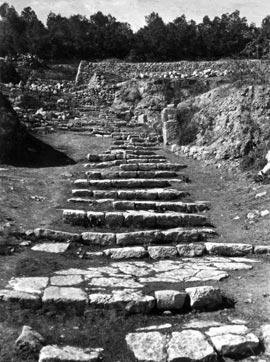

| | | | Archaeological Excavations and Ruins of Settlements and Sites | | | | As far as is known, Raad was the first archeological photographer in the region. He accompanied many western archaeological expeditions either in an official capacity or out of personal interest, or provided them with photographs. For example, the excavations at Beit Guvrin, at Beit Shemesh, in Al Khalīl Heights (Mamre near Hebron), at Beit Shean, Samaria, Mitzpe, Ashkelon, in the Jerusalem area and more. Raad documented extensively excavations, sites and biblical and historical archeological remains, ruins with ornamental archeological and architectural elements, and close-ups of buildings in places considered sacred or biblical. These photographs to some extent reinforced the biblical and holy image of the country and hinted at different aspects of western photography. Thus, for example, Absalom’s Pillar, as well as the photographs of the Crusader Church ruins in Samaria with people positioned alongside it, recall photographs of these places taken by western photographers of the 19th century (such as the Bonfils Family Photographers). The ruins of Kfar Nahum (Capernaum) and the house of Martha and Mary represent examples of photographs with a Christian significance common to western photographers, and were photographed by Raad as well. | | |

Notes

The photograph captions were taken from Raad’s catalogue as originally written.

Raad’s photographs are not dated.

Raad’s name is written in Hebrew and English exactly as he himself wrote it during the years he was active.

His studio was destroyed in the 1948 war, and parts of it were probably looted by Israeli soldiers and passers-by. His negative archive, stored in another building in Jerusalem, was saved and is currently located in the Institute for Palestine Studies in Beirut.

The exhibition and book were made possible through the generous and vital assistance in the research process of George Raad and his family, and the generosity of a collector who chooses to remain anonymous

Press

| | | | Jerusalem Post Magazine, July 9th, 2010 | | | | Haaretz Supplement, September 9th, 2010 | | | | Le Monde, 20.1.2011 (French) | | | | بكرا- Bokra- 20.9.2012 | | | | Hani Hurani, 13.9.21,Al-Arabi-Al-Jadid, "شرقي الأردن مطلع القرن العشرين عبر عدسة خليل رعد" | | |

| | | |  | | C. Raad - Photography studio outside the Jaffa Gate | | | | |  | | Chalil Raad, A Bethlehem Girl | | |  | | Chalil Raad, Jerusalem from the Russian Tower | | |  | | Chalil Raad, Native Children of Banias | | |  | | Chalil Raad, Wheat Field in the Jordan Valley | | |  | | Chalil Raad, Ruth the Gleaner, The caption relates to Ruth, Chapter 2: 2-3

| | |  | | Chalil Raad, Follow Me I Will Make Thee Fisher of Men, The caption relates to Mark, Chapter 1: 17

| | |  | | Chalil Raad, The Mosque, Beit-Shemesh, Beit Shemesh excavations by Dr. Grant, 1928-1933 | | |  | | Chalil Raad, Ancient Hebrew Steps about 2000 Years Old, Kidron excavations | | |

|