| Abstract | | | June 2007 marks 40 years since the Six Days War, one of the most destructive wars of the state of Israel (after 1948), whose repercussions are apparent to this day. In 1967 Israel occupied the Golan Heights, the Sinai Peninsula, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. Following the occupation, the Israeli state went from economic depression and a perception of threatened security to heights of excitement and joy. The quick victory of the war on all fronts, the “unification” of Jerusalem (according to the Israeli terminology), conquering of the territories and a “return” to the holy places of the Jewish people awakened feelings of strength and and pride, which swept up many of the Israeli public, while ignoring the human rights violation, the heavy immoral aspects of the occupation and repressive control over Palestinians life. A year after the war, the 20th Jubilee of the State was celebrated marked by the euphoria of the sweeping victory while highlighting the power of the IDF. In the same year on Independence Day, the IDF held its military parade in Jerusalem, the first parade to take place in the “unified” city, and which was also the victory parade of the war. The magnificent parade, which inaugurated Israeli broadcast television and flauntingly displayed the military might of the State at the end of the first two decades of its establishment, symbolized above all the status of the army in Israeli society. The exhibition and accompanying book examine the place of the war and the military in Israel’s civil and cultural arena, the domination of militarism over Israeli existence and its influence in forming public opinion and the worldview of the Israeli public, especially with regards to the occupation and apartheid of the Palestinian population.

Photography, as a medium for the masses and one of a series of mediating agents in culture, had an important role, as an emissary of society’s ruling elites, in building Israeli nationalism from the earliest days of Zionism. It was one of the central instruments in constructing the Zionist narrative, largely by “inventing” the national past and setting it in the present - normalizing the occupation. Photography that was produced under the protection of controlling and disciplinary mechanisms (the newspaper and album editors, Government Press Office, Directory of Education- Israel Defense Forces, Information Center of the Prime Ministers' Office, etc.) created and normalized power relations. It assisted in the construction of myths and their entrenchment in society, supported the existing social order and served establishment interests. The visual expressions of this after the Six Days War were many: victory albums produced by public and private publishers that came out immediately after the war, many exhibitions, among them the exhibition “So is Power Forged,” organized in 1967 by the information center of the Prime Ministers Office and composed of information designed and mounted on board; photographs in the press; numerous art-crafts which were distributed in commercial quantities and made considerable use of photographs; the penetration of military terminology into civilian language; documentary films produced after the Six Day War, using the latest “national model", the heroic Zionist, who became even more significant in the Six Days War, and which focused on the fighting Israeli collective; and more. All these reflect the euphoria and intoxication of power, which swept up a large part of the Israeli public, who on many occasions lacked critical judgment.

Both the exhibition (shown at the historic Bet Yad Labanim building for the commemoration of fallen soldiers) and the book seek to undermine the myths that appeared following the war, among them: “Israel always strives for peace and wars are forced on her,” “ Like David and Goliath, so Israel fights a war of one against the many,” “The army and its command are at the heart of civilian existence,” “The myth of heroism is the myth that drives the Israeli soldier,” “Society gives meaning and legitimacy to sacrifice and individual loss,” “ The historical right to the land legitimizes the occupation,” and more. They also seek to show how photographs became the drivers of memory and historical, national consciousness, how the Hebrew language was enlisted in the service of national – military aims, how biblical texts helped to build moral justification for the settlement in “greater” Israel by denial of the “other”, and how aggressive viewpoints permeated Israeli existence. Also what was less dealt with in the public discourse in those years became more significant. That is the ignoring of the destructive results of the war, the occupation and the Apartheid of the Palestinians by a large section of the leadership and the population.

In the exhibition and the book, I have chosen to include photographs from establishment archives – the archive of the Government Press Office within the Prime Minister’s Office, from the IDF archive and from victory albums published after the war, which reflect how the mechanisms of power controlled photography and how, through its use, the establishment shaped worldviews. Although the exhibition and the book show photographs from these two establishment archives and from victory albums, many photographs in these archives are by private photographers. These demonstrate how the hegemonic perception influenced the personal and how these perceptions and elements were adopted in the civilian arena.

The book and exhibition dedicate space to alternative voices expressed in Israeli society over the years against the war and its cultural and civil consequences, and against the myths it created, especially in the field of theatre, film, and the plastic arts. Thus, as an example, on the 26th of April 2007 the play by Hanoch Levin, You, Me and the Next War, will be shown at the Museum with the original cast of actors who participated in it when it was first performed in 1968. Hanoch Levine was one of the first to voice scathing criticism against the war and its destructive products – the occupation, the arrogance, the sacrifice of life, the infiltration of militaristic aspects into civilian life and more – also in other plays like Queen of the Bath (1970). Even though many sacred cows have been dispensed with over the years in Israel, You, Me and the Next War still continues to shock, and after the second Lebanon War, it’s as relevant as ever.

Many years passed before photographed views of the occupation consistently entered the daily press and before film directors began to deal with different aspects of the subject. Even though photojournalists photographed in the occupied territories all those years, the routine exposure of the wider public to these photographs and their expressions of defiance became significant mainly with the outbreak of the first Intifada. The exhibition and the book do not give space to press photography that developed in the last decades, even though it contains an important dimension of criticism and protest.

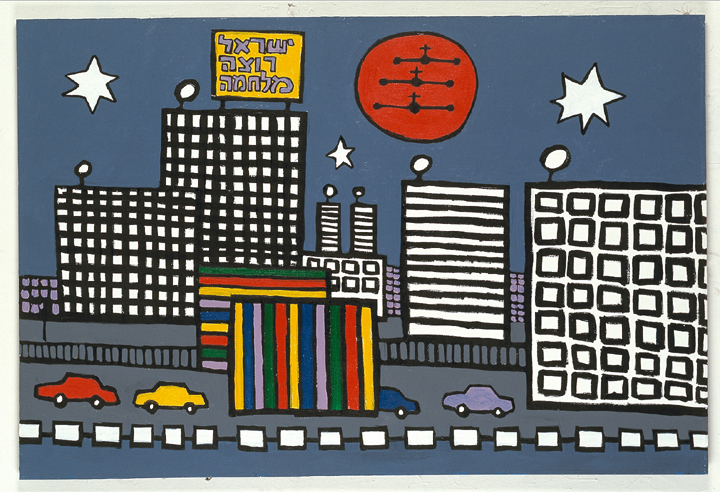

Many artists created works over the years that to some extent oppose the occupation and aspects of militarism that have taken control of Israeli society. Although it appears that their voices have been swallowed up by Israeli indifference, their work has made a growing contribution in building an alternative civilian model to the military one. The exhibition and book do not try to map these expressions systematically but to give them a platform. Thus for example David Reeb, David Tartakover and Meir Gal, who over the years have been consistently active against the occupation and its repercussions and the militarism in Israeli society, show works expressing direct critical messages. Moshe Gershuni’s works, Hi, Soldiers (1980), and Agnus Dei (1980), and works from his series “Wreathes” (1991), deal with the myths of sacrifice, bereavement, the place of the solitary soldier in an oppressive military system, and the torment of the individual family in mourning in a country where national values control sanctity of life. David Reeb shows Israel Wants War (2001) to contrast the myth “Israel always strives for peace,” and Dayan &Arik (1999) which demonstrates how generators of war became cultural heroes. Meir Gal enlarges war decorations to his body’s dimensions indicating how the military takes control of individual existence. Gilad Ophir’s Shooting Targets (from the series “Necropolis,” 1997) expresses, more than anything else, the disillusionment of many Israelis with the central role of the military in Israeli society. The jeep, full of holes, which causes us to freeze and shiver, is like a ghost blowing from the deserts of military maneuvers. Meir Gal locates areas in the civilian arena where war and military terminology have been assimilated into the private sphere establishing an aggresive system of concepts, for example, through the use of street signs (Beit Hanina/Pisgat Zeev 1995-1996 and Yesh Li Ha'huv Besayert Charuv, 1997). Naming streets in Pisgat Zeez after military operations, regiments in the IDF and similar, demonstrate how nationalism and military aggression are present in daily life and how it constructs collective consciousness. Furthermore, the series expresses visually the erasure of Palestinian existence (Beit Hanina) by Jewish settlement (Pisgat Zeev) and demonstrates how the project “return to the land of the fathers” was accomplished in total denial of what was there before.

Other works were created after photographs, posters and documentary films from the Six Days War, and became cultural icons. Thus for example Adi Nes’s photograph Untitled (1999) based on the photograph of a soldier in the Suez Canal with his rifle raised (from Life Magazine); David Tartakover's Crying for Generations (2002), criticizes the long-term occupation by manipulating the most known photograph of the Six Days War taken by David Rubinger (Paratroopers at the Wall); Shuka Glotman’s 1968 Reversed Parade (1999) which screens in reverse the first military parade held in Jerusalem after the war and the work of the Limbus Group Embroideries of Generals (1997) based on posters of IDF generals, which were printed in commercial quantities and hung in many homes and offices, and were distributed chiefly on Independence Day. The action of appropriation and sabotage that Nes, Tartakover, Glotman and Limbus do to these iconic symbols calls for debate on the validity and origin of the above different myths and indicates to a large extent the adoption of aggressive representation which seeped into Israeli culture.

| | | | For the museum web-site | | |

| | | |  | | David Reeb, Israel wants war, 2001, Courtesy of the artist | | |  | | From the Album The Great Victory in Pictures, 1967 | | |  | | Moshe Millner, GPO, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan and Aluf Uzi Narkis at the entrance to Bethlehem , June 1967 | | |  | | Unknown photographer, GPO, One of the Israeli tanks in front of the Mosque on the main square in Bethlehem, June 1967 | | |  | | Shabtai Tal, GPO, An Israeli guard watching Egyptian prisoners of war at El-Arish, 7.6.1967 | | |  | | From the Album, Our War for Peace, 1967 | | |  | | Meir Gal, Ribbons, Courtesy of the artist and Noga Gallery | | |  | | Gilad Ophir, Shooting Targets, from the series Necropolis,1997, Courtesy of the artist and Gordon Gallery | | |

|